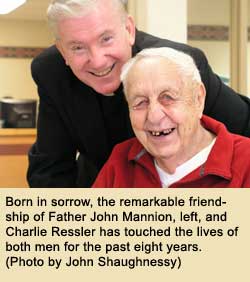

Live, love and learn:

A father’s lessons help priest,

widower form special friendship

By John Shaughnessy

The page came at 10 minutes before midnight, calling Father John Mannion to the hospital room of the dying woman.

The page came at 10 minutes before midnight, calling Father John Mannion to the hospital room of the dying woman.

Entering the room, Father Mannion realized he had never met the woman or her 80-year-old husband who sat by her side, praying that their marriage of 40 years wasn’t coming to an end.

Father Mannion administered last rites to Rita Ressler. And when she died minutes later, the Franciscan priest tried to comfort her husband, Charlie, as he whimpered, “I lost my Rita. I lost my Rita. What am I going to do?”

After Charlie mentioned they had no children, he looked into the eyes of the priest and asked, “Will you help take care of me?”

That question led to a promise—and the beginning of a remarkable relationship between Charlie and Father Mannion, who is the director of spiritual care services at St. Francis Hospital and Health Centers in Beech Grove.

Since that moment eight years ago, Father Mannion has spent a part of nearly every day taking care of Charlie—a connection that continued on a recent morning as the 64-year-old priest drove to see his friend who now lives at St. Paul Hermitage in Beech Grove.

“After Rita died, he would always be at the hospital every night after work—faithfully,” Father Mannion recalled. “He’d be sitting here at my desk or he’d wait on a bench until I came out the door. I’d go over to his house every night and talk to him for an hour or so. He was so lonely. For the past three years, since he’s been at the hermitage, I’ve gone every day, seven days a week, two times a day.”

Pies, blood and faith

As he talked, Father Mannion drove his pickup truck, having lent his car for the week to a couple whose vehicle was in the shop to fix its transmission.

The drive to the hermitage recalled his days as a parish priest—at St. Anne Parish in Monterey, Ind., in the Lafayette Diocese—when he made unusual, extra deliveries as he distributed Holy Communion to the parish’s shut-ins every Friday.

On those days, Father Mannion also brought each of the shut-ins at the small, rural parish their favorite dessert—having spent the previous night cooking in his kitchen, making cinnamon rolls, chocolate cake, and lemon, cherry and apple pies.

The drive to the hermitage also recalled a day from two years ago when he nearly bled to death. On that day, he had been fixing the power mower of a former neighbor—an act of kindness similar to the way he paints houses and cleans gutters for people in need.

“I had my hand under the mower and my left hand went into the sharpened blade,” he recalled. “It severely cut my thumb halfway around. I drove to St. Francis with a floorboard filled with blood. When I got there, I told the doctor I was tired. The doctor said, ‘Sure you’re tired. You left half your blood in the truck.’ ”

After parking at the hermitage, Father Mannion walked inside, where he saw Charlie sitting in his wheelchair with his back to the priest. Father Mannion sneaked toward Charlie and put his hands on his friend’s arms. When the priest came in front of Charlie, Charlie smiled.

“He just lights up when Father comes,” said Benedictine Sister Sharon Bierman, who is the hermitage’s administrator. “Charlie sits and waits for Father. He would not be alive if it wasn’t for Father. I’ve never seen such a faithful caregiver like Father John. I know he’s busy at work, but he always has time for Charlie.”

Father Mannion supervises a staff of 21 people, including 19 full- or part-time chaplains. He chairs the hospital’s institutional ethics committee and reviews hardship cases for employees. It’s a 24-hour, 7-day-a-week job, but he still makes time for Charlie.

A father’s influence

It’s a quality he said he learned from his father.

“When I was ordained, my father, being of Irish descent, was proud,” said Father Mannion, one of seven children. “On my ordination, he said, ‘There are three ‘Ls’ to life and I never want you to forget them: Live, love and learn.’ Then my dad said to me, ‘You know, son, if you combine all three of those, life is always sacred.’

“That has really been my whole priesthood. In order to live, you have to be alive to the moment. To love is the fulfillment of the Gospel. Can you do it for someone else? And to learn is to always be open for growth and change, to always see life as a new beginning.”

Father Mannion said his father, Francis, lived each of those principles. He served the city of Kokomo as a firefighter for 38 years, including 18 as the fire chief. When he retired, he became the executive director of the city’s federally subsidized housing program.

“When my dad died [in 1973], there was a picture on the front page of the Kokomo paper, showing people lined up to pay their respects out the door of the funeral home and down the sidewalk,” he recalled.

“When they came to pay their respects, we heard stories of how he took everyone in the projects a fruit basket at Christmas. People told us how he brought them clothes, gave them this and that, made sure they had heat and how he stopped by when they lost loved ones. That’s why I say that the ordinary things I do are part of me.”

The ordinary things shine through in his care for Charlie, from cutting his meat during lunch at the hermitage to reading him the newspaper, from brushing crumbs off Charlie’s clothes to taking him to the cemetery to visit Rita’s grave.

“We’re good friends,” Charlie said as Father Mannion left his room to get him a cup of ice cream. “I see him every day, every evening.”

The ultimate compliment

Charlie counts on Father Mannion so much that when the priest had back surgery and couldn’t come to visit Charlie, Charlie kept calling people until someone gave him a ride to Father Mannion’s home.

“It’s a very deep, very loving relationship,” said LaRena Brown, Father Mannion’s office manager. “My concern for John is that he thinks so much of Charlie, he doesn’t think of himself. He’s a giver.”

That description is the ultimate compliment to the priest. Even as he said goodbye to Charlie after lunch, he promised to return in the evening to cook dinner for him—“We’re having bacon and macaroni and cheese tonight, Charlie”—just as he always does.

“I put him to bed every night,” Father Mannion said. “When I put him to bed, I always say, ‘I love you, Charlie.’ I started that about three years ago because I’m not sure he’ll be there tomorrow when I come.”

Father Mannion never expected a response to his nightly expression of love. After all, Charlie comes from the same generation of males as the priest’s father, men that have always expressed their love in their actions and their sacrifices rather than their words.

Yet six months ago, Charlie said something that made the priest smile.

“I put him to bed and said, ‘I love you, Charlie.’ His response was a low, ‘Me, too.’ About three or four days later, I said, ‘I love you, Charlie.’ He said, ‘You know that I love you, too.’ ”

Father Mannion smiled as he told that story. His expression didn’t change when he was asked about his dedication to Charlie and whether the eight years—and counting—of daily visits have been worth his time.

“I would do it all over again,” he said. “I wouldn’t question one second. It’s like my father said: ‘Whatever talents God gives you in life, give them away.’ He always felt that in giving we receive. I feel Charlie has given me more than I ever gave him.” †