Sight Unseen / Brandon A. Evans

A sky filled with invisible stars

Lent consistently strikes me as one of the most ill-timed of seasons—an idea that our yearlong pandemic has only served to make more obvious.

Lent consistently strikes me as one of the most ill-timed of seasons—an idea that our yearlong pandemic has only served to make more obvious.

In the U.S., we’ve already endured the long slog through winter: its dark nights, barren trees, cold stars and frigid temperatures. And then, just as springtime starts to fill the air with its heavy, earthy smell and the sun slows its dip into the evening sky—just as the birds begin chirping again and we all breathe a sigh of relief—the Church drives hard in the opposite direction.

She proclaims a fast, and declares the days to become a time for penance and prayer, for reflection on the sorrows of Jesus and the sufferings of the world.

Liturgies become more solemn and the hymns more sparse, the sanctuaries plain and eventually the statues covered.

The whole of Catholicism leans in toward the darkening of Lent.

It seems like a cruel trick, but I think that it’s actually an old trick, one meant to help us celebrate joy more fully. It’s a quirk built right into our human nature: namely, that it’s in the stilling of our senses that we find new depths to them.

The same rule is woven through the fabric of the universe.

Take the night sky, for example.

You have, even on the darkest night and in the most remote of places, never seen but a handful of the stars in our own Milky Way, and beyond that only the faint glow of our closest neighboring galaxies.

We know there is much more out there, but just how much?

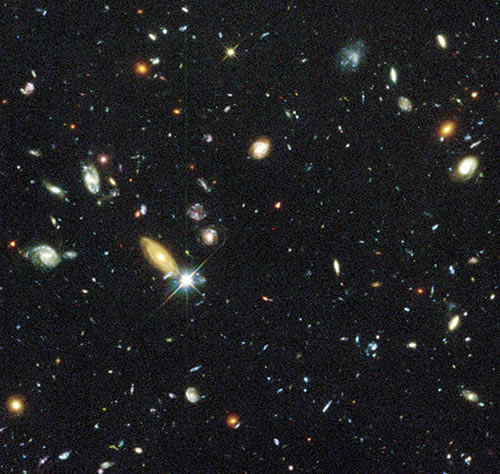

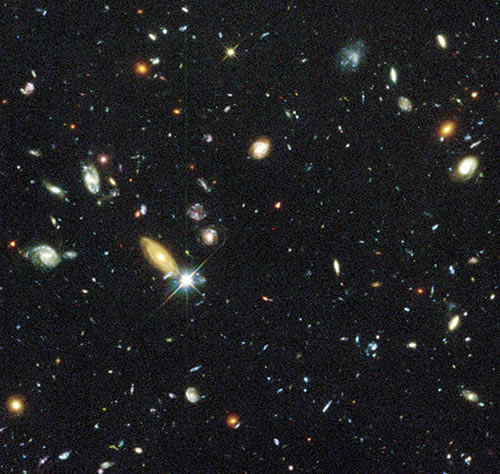

Nearly 30 years ago a team of NASA scientists asked the same question and came up with an idea.

They tasked the Hubble Space Telescope to take the longest exposure ever attempted in photography: to open its camera for more than 100 hours while pointed at a small, dark patch in the constellation Ursa Major.

For 10 days during Christmastime in 1995, Hubble swung around the Earth in silent arcs, opening its lonely eye into a void that looked out past our galaxy. More than 340 times it opened, stared, then closed.

Patiently. Quietly. Consistently. One bit of light at a time.

Finally, the image was processed. What it showed was not a new star—or even a dozen—but whole galaxies whose light had travelled from the distant past and all the way from the edge of the universe to reach us.

And not just a few galaxies, but nearly 3,000 of them, each with worlds and stars and nebulas of untold diversity, all hanging up there in the cosmos—far beyond our reach—as if only to give us the slightest hint of what infinite creativity really means.

Within that experiment there is a lesson, and it’s the same one the Church is driving home during Lent:

Whether it be in our voluntary sacrifices or the ones that are forced upon us by life, there are times when our spirits and senses are called to be still.

It is in those dim nights of the soul that there are stars we can see that no one else can: insights, revelations, visions, stories, dreams—all things that only we are privy to and that the whole world will miss if we don’t find and share them.

It is just one of the purposes of penance and suffering, because beauty—deep beauty—is found not just in the boisterous and luminescent, the obvious and plainly delightful, but also in the faint and delicate, in the small and hidden spaces of our stories. Some splendors can only be seen after one’s spiritual eyes have waited and watched—and grown accustomed to the dark.

This is part of what the Church is doing in Lent, and even more so in the final days before Easter, when all the altars are laid bare and the Good Friday service ends in a silent walk back down the aisle.

The whole Church is hushed; she closes her eyes on Holy Saturday and settles into that night, her sanctuaries darkened and stained-glass wonders obscured.

In that last silence, Easter finally comes at the nighttime vigil, not with clanging bells and Alleluias, nor bright lights, flowers and smiles—not at first, anyway. The triumph of the Resurrection arrives with a single flame processed into a church and shared with each person holding their own taper. For a moment, the light of Christ twinkles softly against the illumined faces of those who have waited and willed just a bit more spiritual winter before allowing in the spring air.

That all Lent is broken by the beauty of a single flame reminds us of what we already know deep down, and have felt in one way or another throughout our own inspirations and experiences:

That each of us is ever walking beneath a sky filled with invisible stars. They are ours to find in the still places of life, and more terribly wonderful, we are their sole bearers to a world which badly needs their light.

(Sight Unseen is a regular column that explores the beauty of God and his creation. Brandon A. Evans is the online editor and graphic designer of The Criterion and a member of St. Susanna Parish in Plainfield.) †

This is just a portion of the Deep Field image taken in 1995 by NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope. Representing a narrow “keyhole” view stretching to the visible horizon of the universe, the image covers a speck of the sky only about the width of a dime 75 feet away. In this small field, Hubble uncovered an assortment of galaxies at various stages of evolution. (Photo credit: R. Williams (STScI), the Hubble Deep Field Team and NASA/ESA)

Lent consistently strikes me as one of the most ill-timed of seasons—an idea that our yearlong pandemic has only served to make more obvious.

Lent consistently strikes me as one of the most ill-timed of seasons—an idea that our yearlong pandemic has only served to make more obvious.